|

The fellow-travellers

climbed down onto the fiery sand of the platform. It was a junction, a junction

of that kind where there is no town for miles, and where the resources of the

railway and its neighbourhood compare unfavourably with those of the average

quarantine station.

The first to

descend was a man unmistakably English. He was complaining of the management

even while he extracted his hand-baggage from the carriage with the assistance

of his companion. “It is positively a disgrace to civilisation,” he was saying,

“that there should be no connection at such a station as this, an important

station, sir, let me tell you, the pivot — if I may use the metaphor — of the

branch which serves practically the whole of Muckshire south of the Tream. And

we have certainly one hour to wait, and Heaven knows it’s more likely to be two,

and perhaps three. And, of course, there’s not as much as a bar nearer than

Fatloam; and if we got there we should find no drinkable whisky. I say, sir, the

matter is a positive and actual disgrace to the railway that allows it, to the

country that tolerates it, to the civilisation that permits that such things

should be. The same thing happened to me here last year, sir, though luckily on

that occasion I had but half-an-hour to wait. But I wrote to The Times a strong

half-column letter on the subject, and I’m damned if they didn’t refuse to print

it. Of course, our independent press, etc.; I might have known. I tell you, sir,

this country is run by a ring, a dirty ring, a gang of Jews, Scotchmen, Irish,

Welsh — where’s the good old jolly True Blue Englishman? In the cart, sir, in

the cart.”

The train gave

a convulsive backward jerk, and lumbered off in imitation of the solitary porter

who, stationed opposite the guard’s van, had witnessed without emotion the

hurling forth of two trunks like rocks from a volcano, and after a moment’s

contemplation had, with screwed mouth, mooched along the platform to his grub,

which he would find in an isolated cottage some three hundred yards away.

In strong

contrast to the Englishman, with his moustache afforesting a whitish face,

marked with deep red rings on neck and forehead, his impending paunchiness and

his full suit of armour, was the small, active man with the pointed beard whom

fate had thrown first into the same compartment, and then into the same hour of

exile from all their fellows.

His eyes were

astonishingly black and fierce; his beard was grizzled and his face heavily

lined and obviously burnt by tropical suns; but that face also expressed

intelligence, strength, and resourcefulness in a degree which would have made

him an ideal comrade in a forlorn hope, or the defence of a desperate village.

Across the back of his left hand was a thick and heavy scar. In spite of all

this, he was dressed with singular neatness and correctness; which circumstance,

although his English was purer than that of his companion in distress, made the

latter secretly incline to suspect him of being a Frenchman. In spite of the

quietness of his dress and the self-possession of his demeanour, the sombre

glitter of those black eyes, pin-points below shaggy eye-brows, inspired the

large man with a certain uneasiness. Not at all a chap to quarrel with, was his

thought. However, being himself a widely-travelled man — Boulogne, Dieppe,

Paris, Switzerland, and even Venice — he had none of that insularity of which

foreigners accuse some Englishmen, and he had endeavoured to make conversation

during the journey. The small man had proved a poor companion, taciturn to a

fault, sparing of words where a nod would satisfy the obligations of courtesy,

and seemingly fonder of his pipe than of his fellow-man. A man with a secret,

thought the Englishman.

The train had

jolted out of the station and the porter had faded from the landscape.

“A deserted

spot,” remarked the Englishman, whose name was Bevan, “especially in such

fearful heat. Really, in the summer of 1911, it was hardly as bad. Do you know,

I remember once at Boulogne—” He broke off sharply, for the brown man, sticking

the ferrule of his stick repeatedly in the sand, and knotting his brows came

suddenly to a decision. “What do you know of heat?” he cried, fixing Bevan with

the intensity of a demon. “What do you know of desolation?”

Taken aback,

as well he might be, Bevan was at a loss to reply.

“Stay,” cried

the other. “What if I told you my story? There is no one here but ourselves.” He

glared menacingly at Bevan, seemed to seek to read his soul. “Are you a man to

be trusted?” he barked, and broke off short.

At another

time Bevan would most certainly have declined to become the confidant of a

stranger; but here the solitude, the heat, not a little boredom induced by the

previous manner of his companion, and even a certain mistrust of how he might

take a refusal, combined to elicit a favourable reply.

Stately as an

oak, Bevan answered, “I was born an English gentleman, and I trust that I have

never done anything to derogate from that estate.

“I am a

Justice of the Peace,” he added after a momentary pause.

“I knew it,”

cried the other excitedly. “The trained legal mind is that of all others which

will appreciate my story. Swear, then,” he went on with sudden gravity, “ swear

that you will never whisper to any living soul the smallest word of what I am

about to tell you. Swear by the soul of your dead mother.”

“My mother is

alive,” returned Bevan.

“I knew it,”

exclaimed his companion, a great and strange look of god-like pity illuminating

his sunburnt face. It was such a look as one sees upon many statues of Buddha, a

look of divine, of impersonal compassion.

“Then swear by

the Lord Chancellor.” Bevan was more than ever persuaded that the stranger was a

Frenchman. However, he readily gave the required promise.

“My name,”

said the other, “is Duguesclin. Does that tell you my story?” he asked

impressively. “Does that convey anything to your mind?”

“Nothing at

all.”

“I knew it,”

said the man from the tropics. “Then I must tell you all. In my veins boils the

fiery blood of the greatest of the French warriors, and my mother was the lineal

descendant of the Maid of Saragossa.”

Bevan was startled, and showed it.

“After the

siege, sir, she was honourably married to a nobleman,” snapped Duguesclin. “Do

you think a man of my ancestry will permit a stranger to lift the shadow of an

eyebrow against the memory of my great-grandmother?”

The Englishman

protested that nothing had been further from his thoughts.

“I suppose

so,” proceeded the other more quietly, “and the more, perhaps, that I am a

convicted murderer.”

Bevan was now fairly alarmed.

“I am proud of

it,” continued Duguesclin. “At the age of twenty-five my blood was more fiery

than it is to-day. I married. Four years later I found my wife in the embraces

of a neighbour. I slew him. I slew her. I slew our three children, for vipers

breed only vipers. I slew the servants; they were accomplices of the adultery,

or if not, they should at any rate not witness their master’s shame. I slew the

gendarmes who came to take me — servile hirelings of a corrupt republic. I set

my castle on fire, determined to perish in the ruins. Unfortunately, a piece of

masonry, falling, struck me on the arm. My rifle dropped. The accident was seen,

and I was rescued by the firemen. I determined to live; it was my duty to my

ancestors to continue the family of which I was the sole direct scion. It is in

search of a wife that I am travelling in England.” He paused, and gazed proudly

on the scenery, with the air of a Selkirk. Bevan suppressed the obvious comment

on the surprising termination of the Frenchman’s narrative. He only remarked,

“Then you were not guillotined?”

“I was not,

sir,” retorted the other passionately. “At that time capital punishment was

never inflicted in France, though not officially abrogated. I may say,” he

added, with the pride of a legislator, “that my action lent considerable

strength to the agitation which led to its re-introduction.

“No, sir, I

was not guillotined. I was sentenced to perpetual imprisonment in Devil’s

Island.” He shuddered. “Can you imagine that accursed Isle? Can your fancy paint

one tithe of its horror? Can nightmare itself shadow that inferno, that limbo of

the damned? My language is strong, sir; but no language can depict that hell. I

will spare you the description. Sand, vermin, crocodiles, venomous snakes,

miasma, mosquitoes, fever, filth, toil, jaundice, malaria, starvation, foul

undergrowth, weedy swamps breathing out death, hideous and bloated trees of

poison, themselves already poisoned by their earth, heat unendurable,

insufferable, intolerable, unbearable (as the Daily Telegraph said at the time

of the Dreyfus case), heat continuous and stifling, no breeze but the

pestilential stench of the lagoon, heat that turned the skin into a raging sea

of irritation to which the very stings of the mosquitoes and centipedes came as

a relief, the interminable task of the day beneath the broiling sun, the lash on

every slightest infraction of the harsh prison rules, or even of the laws of

politeness toward our warders, men only one degree less damned than we ourselves

— all this was nothing. The only amusement of the governors of such a place is

cruelty; and their own discomfort makes them more ingenious than all the

inquisitors of Spain, than Arabs in their religious frenzy, than Burmans and

Kachens and Shans in their Buddhist hatred of all living men, than even the

Chinese in their cold lust of cruelty. The governor was a profound psychologist;

no corner of the mind that he did not fathom, so as to devise a means of

twisting it to torture.

“I remember

one of us who took pleasure in keeping his spade bright — it was the regulation

that spades must be kept bright, a torture in itself in such a place, where

mildew grows on everything as fast almost as snow falls in happier climates.

Well, sir, the governor found out that this man took a pleasure in the glint of

the sun on the steel, and he forbade that man to clean his spade. A trifle,

indeed. What do you know of what prisoners think of trifles? The man went raving

mad, and for no other reason. It seemed to him that such detailed refinement of

cruelty was a final proof of the innate and inherent devilishness of the

universe. Insanity is the logical consequence of such a faith. No, sir, I will

spare you the description.”

Bevan thought

that there had already been too much description, and in his complacent English

way surmised that Duguesclin was exaggerating, as he was aware that Frenchmen

did. But he only remarked that it must have been terrible. He would have given a

good deal, now, to have avoided the conversation. It was not altogether nice to

be on a lonely platform with a self-confessed multiple murderer, who had

presumably escaped only by a further and extended series of crimes.

“But you ask,”

pursued Duguesclin, “you ask how I escaped? That, sir, is the story I propose to

tell you. My previous remarks have been but preliminary; they have no pertinence

or interest, I am aware; but they were necessary, since you so kindly expressed

interest in my personality, my family history — heroic (I may claim it) as is

the one, and tragic (no one will deny it) as is the other.”

Bevan again

reflected that his interlocutor must be as bad a psychologist as the governor of

Devil’s Island was a good one; for he had neither expressed nor felt the

slightest concern with either of these matters.

“Well, sir, to my story! Among the convicts there was one universal pleasure, a

pleasure that could cease only with life or with the empire of the reason, a

pleasure that the governor might (and did) indeed restrict, but could not take

away. I refer to hope — the hope of escape. Yes, sir, that spark (alone of all

its ancient fires) burnt in this breast — and in that of my fellow-convicts. And

in this I did not look so much to myself as to another. I am not endowed with

any great intellect,” he modestly pursued,” my grandmother was pure English, a

Higginbotham, one of the Warwickshire Higginbothams (what has that to do with

his stupidity? thought Bevan) and the majority of my companions were men not

only devoid of intelligence, but of education. The one pinnacled exception was

the great Dodu — ha! you start?”

Bevan had not

done anything of the sort; he had continued to exhibit the most stolid

indifference to the story.

“Yes, you are

not mistaken; it was indeed the world-famous philosopher, the discoverer of

Dodium, rarest of known elements, supposed only to exist in the universe to the

extent of the thirty-thousand and fifth part of a milligramme, and that in the

star called Pegasi; it was Dodu who has shattered the logical process of

obversion, and reduced the quadrangle of oppositions to the condition of the

British square at Abu-Klea. So much you know; but this perhaps you did not know,

that, although a civilian, he was the greatest strategist of France. It was he

who in his cabinet made the dispositions of the armies of the Ardennes; and the

1890 scheme of the fortifications of Luné-ville was due to his genius alone. For

this reason the Government were loth to condemn him, though public opinion

revolted bitterly against his crime. You remember that, having proved that women

after the age of fifty were a useless burden to the State, he had demonstrated

his belief by decapitating and devouring his widowed mother. It was consequently

the intention of the Government to connive at his escape on the voyage, and to

continue to employ him under an assumed name in a flat in an entirely different

quarter of Paris. However, the Government fell suddenly; a rival ousted him, and

his sentence was carried out with as much severity as if he had been a common

criminal.

“It was to

such a man (naturally) that I looked to devise a plan for our escape. But rack

my brains as I would — my grandmother was a Warwickshire Higgin-botham — I could

devise no means of getting into touch with him. He must, however, have divined

my wishes; for, one day after he had been about a month upon the island (I had

been there seven months myself) he stumbled and fell as if struck by the sun at

a moment when I was close to him. And as he lay upon the ground he managed to

pinch my ankle three times. I caught his glance — he hinted rather than gave me

the sign of recognition of the fraternity of Freemasons. Are you a Mason?”

“I am Past

Provincial Deputy Grand Sword-Bearer of this province,” returned Bevan. “I

founded Lodge 14,883, ‘Boetic’ and Lodge 17,212, ‘Colenso.’ And I am Past Grand

Haggai in my Provincial Grand Chapter.”

“I knew it!”

exclaimed Duguesclin enthusiastically.

Bevan began to

dislike this conversation exceedingly. Did this man — this criminal — know who

he was? He knew he was a J.P., that his mother was alive, and now his Masonic

dignities. He distrusted this Frenchman more and more. Was the story but a

pretext for the demand of a loan? The stranger looked prosperous and had a first

class ticket. More likely a blackmailer; perhaps he knew of other things — say

that affair at Oxford — or the incident of the Edgware Road — or the matter of

Esme Holland. He determined to be more than ever on his guard.

“You will

understand with what joy,” continued Duguesclin, innocent or careless of the

sinister thoughts which occupied his companion, “I received and answered this

unmistakable token of friendship. That day no further opportunity of intercourse

occurred, but I narrowly watched him on the morrow, and saw that he was dragging

his feet in an irregular way. Ha! thought I, a drag for long, an ordinary pace

for short. I imitated him eagerly, giving the Morse letter A. His alert mind

grasped instantly my meaning; he altered his code (which had been of a different

order) and replied with a Morse B on my own system. I answered C; he returned D.

From that moment we could talk fluently and freely as if we were on the terrace

of the Cafe de la Paix in our beloved Paris. However, conversation in such

circumstances is a lengthy affair. During the whole march to our work he only

managed to say, ‘Escape soon — please God.’ Before his crime he had been an

atheist. I was indeed glad to find that punishment had brought repentance.”

Bevan himself

was relieved. He had carefully refrained from admitting the existence of a

French Freemason; that one should have repented filled him with a sense of

almost personal triumph. He began to like Duguesclin, and to believe in him. His

wrong had been hideous; if his vengeance seemed excessive and even

indiscriminate, was not he a Frenchman? Frenchmen do these things! And after all

Frenchmen were men. Bevan felt a great glow of benevolence; he remembered that

he was not only a man, but a Christian. He determined to set the stranger at his

ease.

“Your story

interests me intensely,” said he. “I sympathise deeply with you in your wrongs

and in your sufferings. I am heartily thankful that you have escaped, and I beg

of you to proceed with the narration of your adventures.”

Duguesclin

needed no such encouragement. His attitude, from that of the listless weariness

with which he had descended from the train, had become animated, sparkling,

fiery; he was carried away by the excitement of his passionate memories.

“On the second

day Dodu was able to explain his mind. ‘If we escape, it must be by a

stratagem,’ he signalled. It was an obvious remark; but Dodu had no reason to

think highly of my intelligence. ‘By a stratagem,’ he repeated with emphasis.

“‘I have a

plan,’ he continued. ‘It will take twenty-three days to communicate, if we are

not interrupted; between three and four months to prepare; two hours and eight

minutes to execute. It is theoretically possible to escape by air, by water, or

by earth. But as we are watched day and night, it would be useless to try to

drive a tunnel to the mainland; we have no aeroplanes or balloons, or means of

making them. But if we could once reach the water’s edge, which we must do in

whatever direction we set out if we only keep in a straight line, and if we can

find a boat unguarded, and if we can avoid arousing the alarm, then we have

merely to cross the sea, and either find a land where we are unknown, or

disguise ourselves and our boat and return to Devil’s Island as shipwrecked

mariners. The latter idea would be foolish. You will say that the Governor would

know that Dodu would not be such a fool; but more, he would know also that Dodu

would not be such a fool as to try to take advantage of that circumstance; and

he would be right, curse him!’

“It implies

the intensest depth of feeling to curse in the Morse code with one’s feet — ah!

how we hated him.

“Dodu explained to me that he was telling me these obvious things for several

reasons: (1) to gauge my intelligence by my reception of them; (2) to make sure

that if we failed it should be by my stupidity and not by his neglect to inform

me of every detail; (3) because he had acquired the professorial habit as

another man might have the gout.

“Briefly,

however, this was his plan; to elude the guards, make for the coast, capture a

boat, and put to sea. Do you understand? Do you get the idea?”

Bevan replied

that it seemed to him the only possible plan.

“A man like

Dodu,” pursued Dugues-clin,” takes nothing for granted. He leaves no precaution

untaken; in his plans, if chance be an element, it is an element whose value is

calculated to twenty-eight places of decimals.

“But hardly

had he laid down these bold outlines of his scheme when interruption came. On

the fourth day of our intercourse he signalled only ‘Wait. Watch me!’ again and

again.

“In the

evening he manoeuvred to get to the rear of the line of convicts, and only then

dragged out ‘There is a traitor, a spy. Henceforth I must find a new means of

communicating the details of my plan. I have thought it all out. I shall speak

in a sort of rebus, which not even you will be able to understand unless you

have all the pieces — and the key. Mind you engrave upon your memory every word

I say.’

“The following

day: ‘Do you remember the taking of the old mill by the Prussians in ’70? My

difficulty is that I must give you the skeleton of the puzzle, which I can’t do

in words. But watch the line of my spade and my heelmarks, and take a copy.’

“I did this

with the utmost minuteness of accuracy and obtained this figure. At my autopsy,”

said Duguesclin, dramatically, “this should be found engraved upon my heart.”

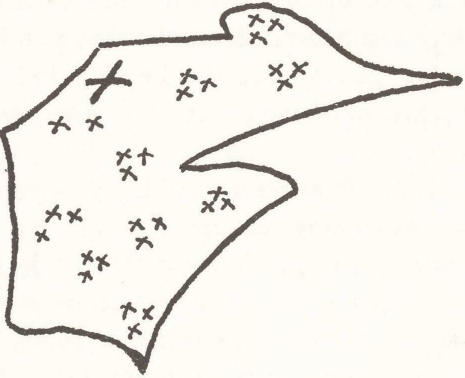

He drew a

notebook from his pocket, and rapidly sketched the subjoined figure for the now

interested Bevan.

“You will note that the figure has eight sides, and that twenty-seven crosses

are disposed in groups of three, while in one corner is a much larger and

thicker cross and two smaller crosses not so symmetrical. This group represents

the element of chance; and you will at least gain a hint of the truth if you

reflect that eight is the cube of two, and twenty-seven of three.”

Bevan looked intelligent.

“On

the return march,” continued Duguesclin, “Dodu said, ‘The spy is on the watch.

But count the letters in the name of Aristotle’s favourite disciple.’ I guessed

(as he intended me to do) that he did not mean Aristotle. He wished to suggest

Plato, and so Socrates; hence I counted A-L-C-I-B-I-A-D-E-S = 10, and thus

completely baffled the spy for that day. The following day he rapped out ‘Rahu’

very emphatically, meaning that the next lunar eclipse would be the proper

moment for our evasion, and spent Pope; the Pompadour; the Stag and Cross.’ ‘The

men of the fourth of September; their leader divided by the letters of the

Victim of the Eighth of Thermidor.’ ‘Crillon was unfortunate that day, though

braver than ever.’

“Such were the indications from which I sought to piece together our plan of

escape!

“Perhaps rather by intuition than by reason, I gathered from some two hundred of

such clues that the guards Bertrand, Rolland, and Monet, had been bribed, and

also promised advancement, and (above all) removal from the hated Island, should

they connive at our escape. It seemed that the Government had still use for its

first strategist. The eclipse was due some ten weeks ahead, and needed neither

bribe nor promise. The difficulty was to ensure the presence of Bertrand as

sentinel in our corridor, Rolland at the ring-fence, and Monet at the outposts.

The chances against such a combination at the eclipse were infinitesimal,

99,487,306,294,236, 873,489 to 1.

“It

would have been madness to trust to luck in so essential a matter. Dodu set to

work to bribe the Governor himself. This was unfortunately impossible; for (a)

no one could approach the governor even by means of the intermediary of the

bribed guards; (b] the offence for which he had been promoted to the

governorship was of a nature unpardonable by any Government. He was in reality

more a prisoner than ourselves; (c] he was a man of immense wealth, assured

career, and known probity.

“I

cannot now enter into his history, which you no doubt know in any case. I will

only say that it was of such a character that these facts (of so curiously

contradictory appearance — on the face of it) apply absolutely. However the tone

of confidence which thrilled in Dodu’s messages, ‘Pluck grapes in Burgundy;

press vats in Cognac; ha!’ ‘The souffle with the nuts in it is ready for us by

the Seine’ and the like, showed me that his giant brain had not only grappled

with the problem, but solved it to his satisfaction. The plan was perfect; on

the night of the eclipse those three guards would be on duty at such and such

gates; Dodu would tear his clothes into strips, bind and gag Bertrand, come and

release me. Together we should spring on Rolland, take his uniform and rifle,

and leave him bound and gagged. We should then dash for the shore, do the same

with Monet, and then, dressed in their uniforms, take the boat of an

octopus-fisher, row to the harbour, and ask in the name of the governor for the

use of his steam yacht to chase an escaped fugitive. We should then steam into

the track of ships and set fire to the yacht, so as to be ‘rescued’ and conveyed

to England, whence we could arrange with the French Government for

rehabilitation.

“Such was the simple yet subtle plan of Dodu. Down to the last detail was it

perfected — until one fatal day.

“The spy, stricken by yellow fever, dropped suddenly dead in the fields before

noon ‘Cease work’ had sounded. Instantly, without a moment’s hesitation, Dodu

strode across to me and said, at the risk of the lash; ‘The whole plan which I

have explained to you in cipher these last four months is a blind. That spy knew

all. His lips are sealed in death. I have another plan, the real plan, simpler

and surer. I will tell it to you tomorrow.’“ The whistle of an approaching

engine interrupted this tragic episode of the adventures of Duguesclin.

“‘Yes,’ said Dodu” (continued the narrator), “‘I have a better plan. I have a

stratagem. I will tell it you tomorrow.’“ The train which was to carry the

narrator and his hearer to Mudchester came round the corner.

“That morrow,” glowered Duguesclin, “that morrow never came. The same sun that

slew the spy broke the great brain of Dodu; that very afternoon, a gibbering

maniac, they thrust him in the padded room, never again to emerge.”

The

train drew up at the platform of the little junction. He almost hissed in

Bevan’s face.

“It

was not Dodu at all,” he screamed, “it was a common criminal, an epileptic; he

should never have been sent to Devil’s Island at all. He had been mad for

months. His messages had no sense at all; it was a cruel practical joke!”

“But how,” said Bevan getting into his carriage and looking back, “how did you

escape in the end?”

“By

a stratagem,” replied the Irishman, and jumped into another compartment.

|